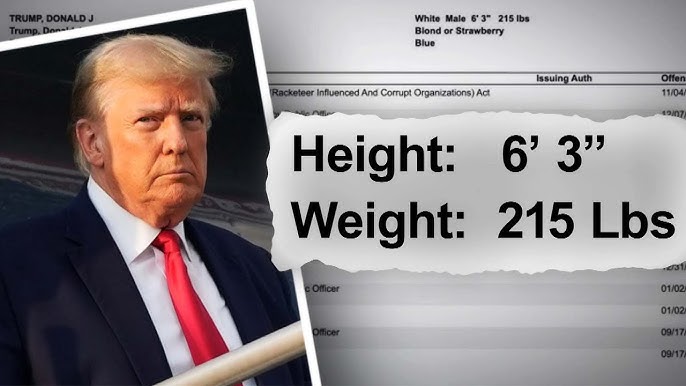

Not to weight shame anyone, but I think many of us were in a state of disbelief when a certain ex-POTUS was arrested in Georgia and the weight listed for him was 215 lbs. For most health professionals, it was very easy to see that Individual #1 was not being honest about his weight. But is he alone when it comes to being dishonest about how much they actually weigh?

Weight, that elusive numerical enigma we confront every now and then, can sometimes feel like it's playing a tantalizing game of hide-and-seek with our expectations. Whether it's the disbelief of an extra pound or two after a weekend of indulgence or the genuine shock of a doctor's scale revealing numbers that seem as fictional as unicorns, the tendency to underestimate our own weight is a puzzle worth exploring.

The frequency with which people underestimate their actual weight can vary based on factors such as demographics, cultural norms, and individual psychological factors. Studies have shown that underestimation of weight is not uncommon. For instance, research conducted in clinical and non-clinical populations has indicated that a significant portion of individuals, particularly those who are overweight or obese, tend to underestimate their weight (Bowring et al., 2012; Duncan et al., 2005). One study conducted in Australia found that among a sample of young people, more than half of participants underestimated their weight, with underestimation being more prevalent among overweight individuals (Bowring et al., 2012). Additionally, studies that focus on body image perceptions and weight-related behaviors have consistently found that a substantial number of individuals perceive themselves to be lighter than their actual weight (Gardner et al., 1996; Linde et al., 2006). This phenomenon can be observed across various age groups and genders.

People may underestimate their weight due to various psychological and cognitive factors. These can include but are not limited to:

1. Body Image and Social Comparisons:

People often base their perceptions of their bodies on social comparisons with others. If they compare themselves to individuals with similar or higher weights, they may perceive themselves as being within a "normal" range. This can lead to underestimation of their own weight. (Brownell et al., 2005)

2. Cognitive Dissonance:

Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals tend to minimize inconsistencies between their beliefs and behaviors. If someone holds the belief that they are leading a healthy lifestyle, they may downplay their weight or convince themselves that their weight is lower than it actually is. (Festinger, 1957)

3. Perceptual Distortion:

Body image distortion can lead to inaccurate perceptions of one's own body size. Individuals who are dissatisfied with their bodies may perceive themselves as larger than they truly are, while those who are satisfied may perceive themselves as smaller. This can lead to underestimation of weight. (Gardner et al., 1996)

4. Social Desirability Bias:

People may provide answers that are socially desirable or acceptable, rather than truthful. Underreporting weight can be a result of wanting to avoid negative judgments or stigmatization associated with being overweight. (Bowring et al., 2012)

5. Unconscious Biases:

Implicit biases related to weight and body image can affect how individuals perceive themselves. Negative biases against overweight individuals may lead people to unconsciously perceive themselves as lighter. (Teachman & Brownell, 2001)

6. Inaccurate Self-Weighing:

People who weigh themselves infrequently or inconsistently may not notice gradual weight changes, leading to underestimation of weight gain. Additionally, variations in clothing, hydration, and time of day when weighing can contribute to inaccuracies. (Linde et al., 2006)

7. Body Dissatisfaction Coping:

Individuals dissatisfied with their bodies may use underestimation as a coping mechanism to manage negative emotions and protect their self-esteem. Downplaying their weight can provide temporary relief from body dissatisfaction. (Svaldi et al., 2014)

Weight gain over time can result from a combination of various factors, including lifestyle choices, biological factors, and environmental influences. It's worth noting that underestimation of weight can have implications for health behaviors and interventions. Individuals who underestimate their weight might not recognize the need for weight management strategies or may not engage in health-seeking behaviors that are appropriate for their actual weight status.

So, the question remains: Are you conning yourself about your weight?

References

Brownell, K. D., Puhl, R. M., Schwartz, M. B., & Rudd, L. (2005). Weight bias: Nature, consequences, and remedies. Guilford Press.

Bowring, A. L., Peeters, A., Freak-Poli, R., Lim, M. S., Gouillou, M., Hellard, M. E., & Stoové, M. A. (2012). Measuring the accuracy of self-reported height and weight in a community-based sample of young people. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 175.

Duncan, D. T., Wolin, K. Y., Scharoun-Lee, M., Ding, E. L., Warner, E. T., & Bennett, G. G. (2011). Does perception equal reality? Weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 20.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Gardner, R. M., Friedman, B. N., & Jackson, N. A. (1996). Body image distortion in college women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20(2), 199-203.

Linde, J. A., Jeffery, R. W., French, S. A., Pronk, N. P., & Boyle, R. G. (2006). Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(3), 210-216.

Teachman, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2001). Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: Is anyone immune? International Journal of Obesity, 25(10), 1525-1531.

Svaldi, J., Griepenstroh, J., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Ehring, T. (2014). Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: A marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Research, 215(3), 761-767.